Critiques of Recent Publications

Note: For an archive of critiques, by topic, CLICK HERE

======================================================

Critique 276 – Alcohol Consumption, High-Density Lipoprotein Particles and Subspecies, and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: Findings from the PREVEND Prospective Study

A protective effect of moderate alcohol consumption for CVD has been reported by numerous studies over decades. This was a key finding of this study too. Further, it is also recognised that alcohol consumption increases high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and this was confirmed by this study too. HDL-C has been considered for years the “good” cholesterol, as suggested by the inverse correlation between its plasma levels and cardiovascular (CVD) risk, as shown by the epidemiology. However, the relationship between HDL and atherosclerosis has been found to be much more complex. This study failed to find an association between alcohol consumption and HDL parameters, suggesting that the clinical relevance of HDL is more related to reverse cholesterol transport in which an inverse relationship has been detected with the prevalence of atherosclerosis, inflammation, and the promotion of plaque stability, as well as the incidence of CV events such as acute myocardial infarction. The ability of HDL to promote reverse cholesterol transport therefore appears to be more related to its size and composition in terms of proteins and lipids, than to HDL-C plasma levels, where identifying efficacy should move to HDL function measurement, that is, reverse cholesterol transport, instead of plasma levels.

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

======================================================

Critique 275 – Recovery of neuropsychological function following abstinence from alcohol in adults diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder: Systematic review of longitudinal studies

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) commonly is associated with compromise in neurobiological and/or neurobehavioral processes. The severity of this compromise varies across individuals and outcomes, as does the degree to which recovery of function is achieved. Clinicians have commented that some of the greatest recoveries are in AUD, where a potentially life-threatening situation has been turned around by clinical intervention coupled with an individual’s determination and peer support. This paper provides clear evidence that alcohol’s compromising effects on neuropsychological function can be improved with abstinence.

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

======================================================

Critique 274 – Multi-ancestry study of the genetics of problematic alcohol use in over 1 million individuals

Problematic alcohol use (PAU) often seems to run in families, and genetics certainly influence our risk or likelihood of developing PAU. Research shows, however, that genes are responsible for about half of the risk for PAU, and hence do not alone determine whether someone will develop PAU. Environmental factors, as well as gene and environment interactions account for the remainder of the risk. Further, multiple genes play a role in a person’s risk for developing PAU and there are genes that increase a person’s risk, as well as those that may decrease that risk, directly or indirectly.

This study involving approximately 1 million individuals uncovered a shared genetic basis for PAU across diverse genetic backgrounds. One hundred and ten risk gene regions were identified, broadening our understanding of PAU’s genetic architecture and its consequences. For example, genetic correlations with other mental and neurological disorders were suggested as well as PAU’s role as a major cause of other health problems and death. Indeed, genome-wide data may pave the way for personalized risk assessments and innovative interventions and pharmacological treatments.

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

======================================================

Critique 273 – Circulating metabolites may illustrate relationship of alcohol consumption with cardiovascular disease

Two papers were recently published which consider the complexity of liver and gut-generated circulating metabolites of alcoholic beverages, such as wine, and their specific roles in human health (referred to as metabolomics). These papers collectively suggest that the 60 or more alcohol-associated metabolites following consumption, may be related to the risk of cardiovascular and other diseases.

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

======================================================

ISFAR reiterates its defence of moderate alcohol consumption’s health benefits by Stockley et al.

ISFAR was invited to provide a commentary on the paper, Apologizing for the alcohol industry? A comment on ISFAR’s defence of alcohol’s purported health benefits by Stockwell et al. (2024) which is available in the Journal of Studies in Alcohol (JSAD) site: doi.org/10.15288/jsad.23-00193. It was duly accepted for publication.

An excerpt from the text which is reproduced with the journal’s permission is available here.

======================================================

Critique 272 – New perspectives on how to formulate alcohol drinking guidelines

To encourage moderate alcohol consumption, many governments have developed guidelines for alcohol consumption. There has been, however, a remarkable lack of agreement about what constitutes an alcohol consumption that is associated with an acceptable risk, optimal health or safe (no risk) alcohol consumption. There is also no consensus on drinking on a daily basis, on a weekly basis and when driving and no consensus about the ratios of consumption guidelines for men and women. In addition, there is no consensus on a strategy with which to develop guidelines. The panel outlines a possible methodology for guideline development internationally to reduce the previously observed lack of consensus. The outlines discussed in the paper’s ‘propositions to debate’, however, are based on very complex non-transparent mathematical modelling of which the evidence base is flawed. The resulting guidance itself has been criticised as confusing for consumers, amongst other issues, and will thus not apply to any other country.

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

======================================================

Critique 271 – Moderate alcohol consumption, types of beverages and drinking pattern with cardiometabolic biomarkers in three cohorts of US men and women

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain the leading cause of death globally, and leading risk factors for CHD and stroke include high blood pressure, high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, diabetes, smoking and second-hand smoke exposure, obesity, unhealthy diet, and physical inactivity.

Various randomized controlled trials have previously identified biomarkers that change with moderate alcohol consumption and which may explain its beneficial effects on CVDs. These biomarkers include HDL cholesterol, glycaemic control as HbA1c and adiponectin. Other relevant biomarkers changing with moderate alcohol consumption are fibrinogen, fibrinolysis, platelet aggregation, other lipoproteins, such as LDL cholesterol, HDL functionality, oxidative markers and triglycerides. This large epidemiological study provides further support for these beneficial effects but also highlights the beneficial effects on and inflammatory markers. The study also supports the importance of a regular and moderate pattern of alcohol consumption, not abstinence nor binge or heavy drinking, to maintain cardioprotection.

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

======================================================

Critique 270 – Alcohol consumption and prognosis and survival in breast cancer survivors: the Pathways Study

Lifestyle in general appears to be very important in reducing the risk for breast cancer. There is a paucity of sound scientific information and advice available to women post-breast cancer diagnosis and treatment as to whether they could continue to consume alcohol without adversely affecting their health. This study adds to the existing evidence that pre- or post-diagnostic alcohol consumption is not positively associated with breast cancer re-occurrence. It also suggests that light to moderate alcohol consumption may in fact be beneficial to these women’s health, especially for those with an unhealthy BMI, allied with a healthy diet and regular exercise.

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

======================================================

Critique 269 – Global prevalence, incidence, and outcomes of alcohol related liver diseases: a systematic review and meta‑analysis

In general terms, the risk of alcohol-related liver disease (ARLD) increases with how much you drink and how often you drink. Liver disease can take the form of fatty liver disease, alcoholic hepatitis and alcoholic cirrhosis.

A definitive threshold below which alcohol intake will not cause liver disease has not been established, but levels of around 20-30 g/day for men and 10-15 g/day for women are unlikely to cause ARLD in most individuals. As both quantity and frequency of influences the risk of ARLD, regular heavy drinkers and alcohol dependent drinkers are at risk of and die from ARLD at a much higher rate than the general population.

This extensive systematic review and meta‑analysis summarises the usually small-scale studies on ARLD to describe the ARLD population (Niu et al., 2023). Accordingly, it provides insight in the global prevalence of ARLD which is currently estimated at 4.8%, and the role of factors influencing the disease such as gender, ethnicity, tobacco smoking, obesity, and chronic viral hepatitis C. The relationship between ARLD prevalence or incidence and alcohol consumption data in a specific country were, however, not investigated.

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

======================================================

Critique 268 – Alcohol intake including wine drinking is associated with decreased platelet reactivity in a large population sample – 1 August 2023

This study by Pashek et al. (2023) confirms previously observed associations between alcohol consumption and decreased platelet reactivity, but does not conclusively confirm differential beverage and gender effects.

Our knowledge regarding the health effects of alcohol consumption might best be grouped into two complementary approaches. Observational studies, for example, have now reached epic proportions in sample size and duration, and feeding studies have assessed the immediate and short-term effects of alcohol on behaviour, biochemical pathways, and similar social or physiological endpoints. Clearly, neither of these approaches represents gold-standard evidence in biomedical research, that is, only a long-term randomized trial of clinical endpoints would meet that standard. Existing clinical trial and epidemiological evidence as well as confirmatory studies such as Pashek et al. (2023) provide useful insight into the endpoints that a clinical trial of moderate alcohol consumption might be best poised to tackle (Mukamal et al. 2016).

These observational data have demonstrated a differential effect of the alcoholic beverages on haemostatic cardioprotective mechanisms. More data are required, however, to establish the degree of differentiation between alcoholic beverages in conferring cardio-protection, cancer-protection and protection against other degenerative diseases.

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

======================================================

Critique 267 – Alcohol consumption and risks of more than 200 diseases in Chinese men – 11 July 2023

This paper essentially suggests that alcohol abuse leads into a broad array of diseases in a primarily unhealthy elderly population of Chinese men who consume large amounts of alcohol. In that sense, it may have been more appropriate to title the paper “Alcohol abuse and risks of more than 200 diseases in apparently unhealthy Chinese men. It adds little new insight in the already existing knowledge on alcohol consumption, and especially light to moderate alcohol consumption, and health in the Chinese populations, despite the additional Mendelian Randomisation (MR) analyses undertaken.

MR uses genetic variation as a natural experiment to investigate the causal relations between potentially modifiable risk factors such as alcohol and health outcomes in observational data.

Even though many more genetic factors have been identified for inclusion in these MR analyses it is clear that the results from many different types of studies must be considered when attempting to judge the health effects of alcohol. This is especially the case because type of beverage, drinking patterns, tobacco smoking and other lifestyle habits, diet, and many other environmental factors relate to the effects of alcohol consumption. Thus, the combination of data from observational studies, clinical trials, animal experiments, and MR analyses will be needed to improve our knowledge on the relationship between alcohol consumption to health and disease in all populations.

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here

======================================================

Critique 266: Reduced stress-related neural network activity mediates the effect of alcohol on cardiovascular risk – 3 July 2023

Well-known and studied causes of cardiovascular diseases include genetic, environmental, dietary and lifestyle components. Stress can be considered as a lifestyle component and risk factor for cardiovascular disease. The amygdala region of the brain is associated with stress responses via the sympathetic nervous system, and duly increases blood pressure and heart rate, and triggers the release of inflammatory cells to stressors. This study has focused on the role of alcohol in mitigating these adverse effects from stress on the cardiovascular system. The study showed that light to moderate alcohol consumption of 1 to 2 standard drinks daily compared to abstinence potentially lowers cardiovascular risk as it leads to long-term reductions in the brain’s stress signalling in the amygdala. The relationship is also j-shaped where heavier alcohol consumption, however, increases the risk of stress-related cardiovascular disease events. This is a new plausible mechanism of action for alcohol on reducing cardiovascular risk which deserves further study.

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here

======================================================

Critique 265 – Alcohol consumption and breast cancer prognosis after breast cancer diagnosis: a systematic review and meta‑analysis of the Japanese Breast Cancer Society Clinical Practice Guideline, 2022 edition – 14 June 2023

According to the WHO, there are more than 2.3 million cases of breast cancer diagnosed each year, which make it the most common cancer among adults. In 95% of countries, breast cancer is the first or second leading cause of female cancer deaths (https://www.who.int/news/item/03-02-2023-who-launches-new-roadmap-on-breast-cancer). Initial meta-analyses such as that of Longnecker et al. (1988) clearly showed risk at higher rates of alcohol consumption, but mixed results at moderate rates, depending on the model. This meta-analysis of 33 more recent studies, however, clearly shows no elevated risk at moderate consumption levels. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, we should continue to discourage heavy consumption because it is likely to be associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, not to mention many other health risks. This report, however, should relieve light to moderate alcohol drinkers of the fear of increasing their risk of breast cancer, and confirm that moderate consumption reduces overall mortality risk as also shown in this meta-analysis.

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here

======================================================

Critique 264 – Association Between Daily Alcohol Intake and Risk of All-Cause Mortality. A Systematic Review and Meta-analyses – 26/4/2023

Zhao et al. (2023) again claims as did Stockwell et al. (2016) that “the importance of controlling for former drinker bias/misclassification is highlighted once more in our results which are consistent with prior studies showing that former drinkers have significantly elevated mortality risks compared with lifetime abstainers”. This statement clearly contradicts their e-Figure 4 which shows a J-shaped relationship between alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality, such that, as succinctly summarised by Forum Member Djousse, “scientific inference suffers greatly when objective reporting of data is ignored by some authors”. Zhao’s claim was made based on just 20 additional papers included in their analysis which carefully excluded hundreds of validated studies showing reduced disease and all-cause mortality among moderate drinkers, as well as choosing occasional drinkers as the reference group.

The key features that clearly demonstrate bias in the present paper are:

1. This is the third attempt by the same group of researchers to disprove the beneficial relationship between light to moderate alcohol consumption and cardiovascular health. The first attempt (Fillmore et al, in 2006) was discredited by reanalysis of the studies. Reanalysis showed that after adjusting for the claimed bias the cardioprotective effect for regular light to moderate alcohol consumption was still apparent.

2. Numerous meta-analyses have been undertaken over the past 15 years that have adjusted for this proposed bias and they have consistently shown that there is a cardioprotective effect for regular light to moderate alcohol consumption.

3. In this new paper, Zhao et al., (2023) have again biased their meta-analysis by ‘cherry picking’ a small number of studies for their meta-analysis – they discarded 3230 studies and analysed only 107. The 107 studies selected did relate consumption to disease and all-cause mortality but the authors carefully avoided hundreds of validated studies that showed reduced disease risk among light to moderate drinkers.

4. Countless animal and human studies over the past four decades have provided extensive evidence for the biological mechanisms supporting the findings that light to moderate alcohol consumption is cardioprotective. Zhao et al., (2023) seem to have deliberately pretended that they do not exist.

Forum Member Skovenborg succinctly summaries this flawed further meta-analysis by the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research group to discredit the positive association between regular low to moderate alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality as follows: “a well-designed meta-analysis can provide valuable information for researchers, policymakers, and clinicians. However, there are many critical caveats in performing and interpreting them, and thus many ways in which meta-analyses can yield misleading information. Meta-analysis is powerful but also controversial— controversial because several conditions are critical to a sound meta-analysis, and small violations of those conditions can lead to misleading results (Walker et al. 2008).”

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here

======================================================

Critique 263 – Alcohol Drinking Patterns and Risk of Developing Acute and Chronic Pancreatitis – 17/04/2023

Alcohol consumption has often been found to be a risk factor for acute pancreatitis (AP) and a number of biologic mechanisms for such an association have been suggested. Overall, however, the risk is rather low, as only 1-3% of heavy drinkers develop AP after 10-20 years of follow up.

This is the second study of the Danish National Health Surveys group investigating the association between drinking pattern and pancreatitis. A prospective cohort study based on data from 316,751 men and women participating in the Danish National Health Surveys 2010 and 2013, it specifically assessed the effects of type of alcohol as well as drinking pattern on risk of acute and chronic pancreatitis.

A J-shaped association between the consumption of alcohol and development of pancreatitis was observed particularly for beer and spirits where drinking frequency such as daily, frequent binge drinking and problematic alcohol use were associated with increased development of pancreatitis. The study is important because of its large number of subjects, apparently good ascertainment of disease, appropriate and well-described methodology, and the fact that data on the type of beverage were available. Further, it was carried out using data from subjects in a single country, thus is less likely to be confounded by mixing data from very divergent cultures.

Placed in perspective, however, both acute and chronic pancreatitis risk was shown to increase at higher levels of alcohol consumption, at leveles well above the definitions for moderate alcohol consumption. Furthermore, beverage type does not seem to be an important modulator of this risk, whereas problematic alcohol use was, even for the alcohol consumption adjusted hazard ratios.

Forum Member Professor R Curtis Ellison suggested that “while this paper on the relation of alcohol to pancreatitis mainly supports previous research on the topic, it is important due to its large number of subjects, apparently good ascertainment of disease, appropriate and well-described methodology, and the fact that data on the type of beverage were available. Further, it was carried out using data from subjects in a single country, thus is less likely to be confounded by mixing data from very divergent cultures… The key findings of this well-done study are that heavy drinking is associated with increases in risk of pancreatitis, whereas drinking within recommended guidelines for any beverage appears to not increase the risk.”

Concluding comments

Altogether, an interesting study that shows that acute and chronic Pancreatitis increases at higher levels of alcohol consumption, at least well above the definitions for moderate alcohol consumption. Beverage type does not seem to be an important modulator of this risk, whereas problematic alcohol use was, even for the alcohol consumption adjusted hazard ratios.

Reference:

Alcohol Drinking Patterns and Risk of Developing Acute and Chronic Pancreatitis

Authors. Becker U, Timmermann A, Ekholm O, Grønbæk M, Drewes AM, Novovic S, Nøjgaard C, Olesen SS, Tolstrup JS. 2023. Alcohol and Alcoholism Mar 1;agad012. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agad012. Online ahead of print, 10pp.

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here

======================================================

Critique 262 – Changes in alcohol consumption and risk of dementia in a nationwide cohort in South Korea

Cognitive dysfunction eventually leads to a loss of independence that becomes a burden on families and society, as the individual requires more intense care and often institutionalisation. In the later stages, the cognitive impairment associated with dementias will create total dependency such that dementia is one the major causes of disability and disability burden overall among older adults globally (WHO 2023)[1].

As there is no cure, identification of factors associated with preservation of cognitive function could lead to substantial improvements in the quality of life in older adults, including simple dietary measures. Recent systematic review of health behaviours which maintain healthy cognitive function suggests that the consumption of fish and vegetables[2],[3], moderate physical activity and moderate alcohol consumption tend to be protective against cognitive decline and dementia. Studies have shown that alcohol acts directly and indirectly on the brain[4].

Consistent with the systematic review of 28 studies by Rehm et al. (2019)[5] where although causality could not be established, light to moderate alcohol consumption in middle to late adulthood was associated with a decreased risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. Conversely, heavy alcohol consumption was associated with changes in cognitive impairments, and an increased risk of all types of dementia.

Jeon et al. (2023) also showed in their massive retrospective cohort study of four million people followed for six years resulting in 24 million person-years, which is a significantly adds to the strength of the study outcomes that a decreased risk of dementia was associated with maintaining mild to moderate alcohol consumption. The study additionally showed that a decreased risk of dementia was associated with reducing alcohol consumption from a heavy to a moderate level, and with the initiation of mild alcohol consumption; collectively this data suggests that the threshold of alcohol consumption for dementia risk reduction is low.

Genetic profiles, standardized cognition, mood and behavioural assessments, as well as the quantification of structural and functional connectivity brain measures, which are all well established for dementia, if included in this study would have enabled the extrapolation of, and further added to the global relevance of the results from this huge South Korean population.

Forum members agreed with the conclusions of the authors which, simply stated, suggest that ‘sustained’ drinking up to 30 g/day is good for the brain, but non-drinkers who went from zero to moderate or heavy drinking did not show the same improvement as those who increased only to mild drinking. These observations are not new and indeed are generally consistent of those of past studies on alcohol consumption and cognitive decline, but the subject size is almost more significant than the sum of participants in past studies.

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here

[2] Gardener SL, Rainey-Smith SR, Barnes MB, Sohrabi HR, Weinborn M, Lim YY, Harrington K, Taddei K, Gu Y, Rembach A, Szoeke C, Ellis KA, Masters CL, Macaulay SL, Rowe CC, Ames D, Keogh JB, Scarmeas N, Martins RN. Dietary patterns and cognitive decline in an Australian study of ageing. Mol Psychiatry. 2014 Jul 29. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.79.

[3] van de Rest O, Berendsen AA, Haveman-Nies A, de Groot LC. Dietary patterns, cognitive decline, and dementia: a systematic review. Adv Nutr. 2015; 6(2):154-68.

[4] Brust JC. Ethanol and cognition: indirect effects, neurotoxicity and neuroprotection: a review. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2010; 7(4):1540-1557

[5] Rehm, J., Hasan, O.S.M., Black, S.E. et al. Alcohol use and dementia: a systematic scoping review. Alz Res Therapy 11, 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-018-0453-0

======================================================

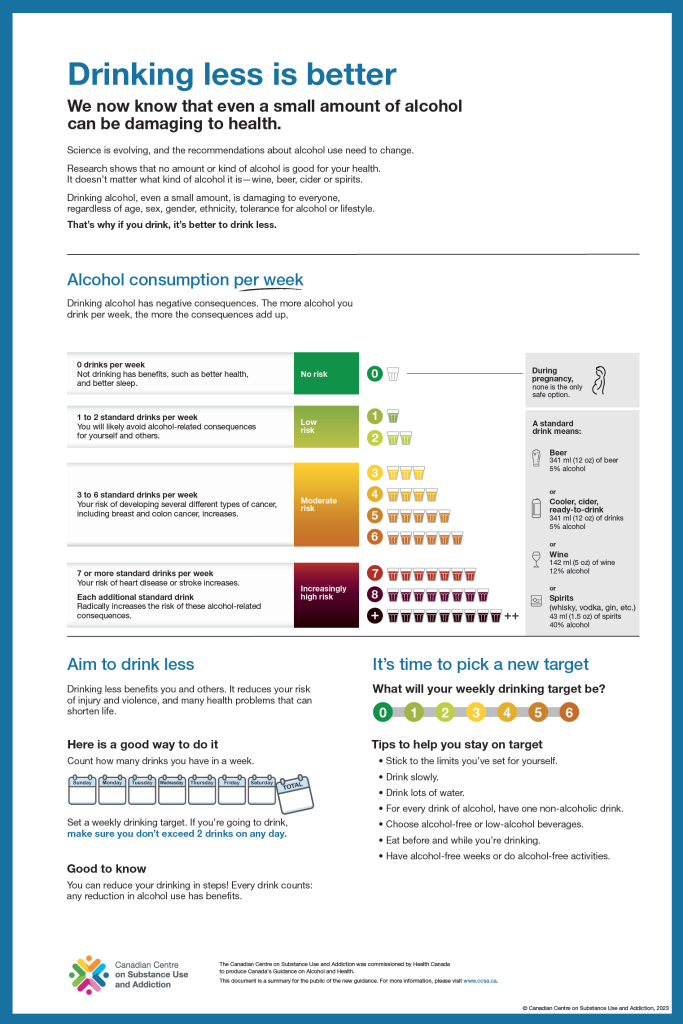

Critique 261: Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Authors: Paradis, C., Butt, P., Shield, K., Poole, N., Wells, S., Naimi, T., Sherk, A., & the Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines Scientific Expert Panels.

In January this year, the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA) issued its recommendations entitled: Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report[1]. The Final Report contains three documents produced for three different target groups, namely one public summary for the general public, a technical summary for health professionals and a technical report for alcohol scientists. The public summary, entitled “drinking less is better” and subtitled “we know that even a small amount of alcohol can be damaging” states that science is evolving so that recommendations about alcohol need to change and that even a small amount of alcohol is damaging to everyone.

The recently issued Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health by the CCSA focuses primarily on risk of death estimated by modelling twenty-one disease-alcohol consumption associations. The scientific evidence relating to both abusive and moderate alcohol consumption is itself not sufficiently consistent to produce precise recommendations for safe drinking for every alcohol consumer. There is no clear scientific evidence that uniformly applies to all population groups.

The accompanying Final Report suggests that “evidence has changed since the release of the 2011 Canadian Low Risk Drinking Guidelines”. This evidence includes the relationship between alcohol and cancer per se, stating that there is now no lower risk threshold for alcohol consumption; this contradicts 2022 data from 142,960 individuals from the population-based study MORGAM Project, that shows that there is indeed a nadir of the association. The authors also state that there is now no lower risk threshold for hypertension which was not shown in the reference that was used in the mathematical risk modelling. Additionally, they state that the potential cardioprotective effect of light to moderate alcohol consumption is more uncertain than previously estimated, which again was not shown in the reference selectively cited; this reference actually highlighted that relevance of drinking pattern in mathematical modelling. Other recent references cited are also considered contentious. This is not new data since 2011.

Forum members consider it a major omission not to take into account the association of alcohol consumption with overall mortality and only base their guidelines on an internationally criticized model. Moreover, the model mainly used evidence of low to very low quality. The authors also chose not to differentiate between gender and downplayed the reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and some other diseases like type II diabetes mellitus, nor did the authors take underreporting into account. Further, the authors neglected drinking pattern in their modelling which impacts risk of both short- and long-term alcohol-related harms and more importantly differentiates protective from harmful levels of alcohol consumption. The Forum also noticed several cases of misinterpretation of the input used for their modelling. Interestingly while these significant limitations were listed in the accompanying technical report, they were completely ignored in generating the long-term risk estimates for death and disability for Canadian alcohol consumers. In addition, the Forum noted that members of the Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines Scientific Expert Panels and their associates are also authors of regularly cited references in the accompanying Final Report, certain of which are contentious and consistently use now widely debunked arguments around the ‘sick quitter’ hypothesis.

Accordingly, the Forum believes that these recommended guidelines do not contribute to their own intention to allow Canadians to make well-informed decisions on alcohol use and how it will affect their health. Furthermore, the evidence base assessing all-cause mortality and the risk of mortality from any cause at the 2011 alcohol level of 134.5 g/week for women, with no more than 27 g/day most days and 202 g/week for men, with no more than 40 g/day most days, remains robust and the hence the 2011 guidelines remain relevant to Canadians rather than the 2023 CCSA recommendations.

[1] https://www.ccsa.ca/canadas-guidance-alcohol-and-health-final-report

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here

======================================================

Critique 260: Two studies on the Mediterranean alcohol-drinking pattern and its association with hypertension and all cause mortality in the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra” (SUN) cohort – 24 January 2023

Mediterranean Alcohol-Drinking Patterns and All-Cause Mortality in Women More Than 55 Years Old and Men More Than 50 Years Old in the “Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra” (SUN) Cohort – 14 December 2022

Mediterranean Alcohol-Drinking Pattern and Arterial Hypertension in the “Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra” (SUN) Prospective Cohort Study – 7 January 2023

The SUN (Seguimiento Universidad De Navarra) study represents one of the main cohorts in the European Mediterranean area aiming to explore the association between dietary factors and non-communicable diseases. The SUN study had previously shown that better adherence to the Mediterranean diet, which includes moderate alcohol consumption with meals, was significantly associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality. It was also significantly associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), which is the leading global cause of premature mortality.

These two new papers from the SUN study cohort concern alcohol and its potential beneficial effects when part of a Mediterranean diet and lifestyle. One paper is related to all-cause mortality in an older adult subset of the cohort, while the other related the pattern of drinking to the risk of an initial diagnosis of hypertension, which is a modifiable risk factor for atherosclerosis and therefore CVD.

Limitations of both studies include the relatively small number of events in some groups of drinkers and abstainers, where the latter group included both former drinkers and lifelong abstainer which are usually separated to reduce potential confounding. The all-cause mortality results may also be limited to a certain degree by a relatively small number of non-drinkers (n=35, for whom the degree of compliance with the Mediterranean diet was not shown), and the small number of drinkers who had low compliance with the Mediterranean Drinking Pattern (n=35), with the latter chosen as the reference group. Similarly, a weakness of the hypertension study is that the number of subjects in the low-adherence group was much smaller (n=156) compared with the other groups, yet it served as the referent category in the analyses. Further the low-adherence group was more likely to be younger, male, binged more, smoked more, consumed more alcohol and sugar-sweetened beverages, reported more recent weight gain, and had other unhealthy characteristics. While the investigators used multi-variable analyses that attempted to adjust for these factors, residual confounding is always a problem. Thus, it will be important that further studies with a larger number of subjects in the referent group confirm the observed relations shown in this study. According to their results, however, it seems clear that a drinking pattern of regular, moderate, wine consumption with food does not increase the risk of hypertension, an important message for the health of the population.

Overall, Forum members agreed with the conclusions of the authors that “Moderate red wine consumption at meals which is spread throughout the week, avoiding binge drinking, reduces the risk of all-cause mortality by 48%. These results are consistent with individual studies of each separate aspect of the pattern and with studies of a priori patterns.” Further, this paper strongly suggests that assessments of the relation of alcohol consumption to health should focus on the pattern of drinking, not just the total amount consumed.

References: Barbería-Latasa M, Bes-Rastrollo M, Pérez-Araluce R, Martínez-González MÁ, Gea A. Mediterranean Alcohol-Drinking Patterns and All-Cause Mortality in Women More Than 55 Years Old and Men More Than 50 Years Old in the “Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra” (SUN) Cohort. Nutrients. 2022 Dec 14;14(24):5310. doi: 10.3390/nu14245310. PMID: 36558468; PMCID: PMC9788476.

Hernández-Hernández A, Oliver D, Martínez-González MA, Ruiz-Canela M, Eguaras S, Toledo E, de la Rosa PA, Bes-Rastrollo M, Gea A. Mediterranean Alcohol-Drinking Pattern and Arterial Hypertension in the “Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra” (SUN) Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients. 2023; 15(2):307. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15020307

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here

======================================================

Critique 259: Importance of consuming alcohol (especially wine) with meals in relation to the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus – 30 November 2022

Essentially all previous epidemiologic studies have shown that subjects who consume alcohol are at a lower risk than abstainers of developing Type 2 diabetes mellitus. The present analysis provides new information from more than 300,000 subjects in the UK BioBank who reported that they were consumers of alcohol; it demonstrates how the pattern of consuming alcohol plays an important role in the effect of alcohol on the risk of diabetes. Consuming an alcoholic beverage with food, versus drinking it at other times, is associated with a considerably lower risk of diabetes mellitus. This effect in independent of the amount of alcohol consumed, which suggests that all alcohol policy should be based only on research in which the pattern of drinking is known.

The study also demonstrated that the protective effects against diabetes was greater for consumers of wine rather than for those consuming beer or spirits. These associations are consistent with most previous epidemiologic studies, and now supported from these analyses of a very large cohort.

The authors had very reasonable estimates of alcohol intake as well as good ascertainment of health outcomes. They also had considerable data on many lifestyle and social factors that relate to the development of diabetes, so that confounding and modification of effect by them could be dealt with in the analyses. Forum members noted some limitations to the analytic methods regarding categorization of subjects by the type of alcohol they consumed, and the failure to adjust for diet. However, overall the results appear to support well the conclusions of the authors that there are key health advantages in terms of the risk of developing diabetes of consuming alcoholic beverages (especially wine) with meals, rather than on an empty stomach.

Reference: Ma H, Wang X, Li X, Heianza Y, Qi1 L. Moderate alcohol drinking with meals is related to lower incidence of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr 2022;0:1–8.

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here

Critique 258. Do the calories in alcoholic beverages increase the risk of obesity? 2 November 2022

This study was designed to determine if greater emphasis on the role of alcohol consumption as related to body weight might lead to less drinking and have a beneficial effect on subsequent weight and obesity. It was based on a survey of a select group of Australian adults who had previously volunteered to take part in medical research (not a population-based cohort). The authors took data from subjects who agreed with a question that asked if the subject ever thought about decreasing alcohol intake to lose weight, comparing them with those who did not answer the question in the affirmative. They compared the two groups (those answering yes versus those answering no to this question) and found some relation with body weight and with BMI (the latter of which was based on self-report of subjects regarding their height and weight).

Unfortunately, the premise that any alcohol increases body weight is erroneous, as the investigators ignored current scientific data that has consistently shown that light-to-moderate alcohol consumption does not increase body weight (which is seen generally only with excessive alcohol intake or binge drinking). While the authors had detailed data on the number of drinks reported by subjects, they ended up categorizing drinking levels into only two groups: ‘daily or weekly,’ or ‘monthly,’ which make it impossible to evaluate results of realistic drinking levels. They present no data on the pattern of drinking (e.g., with or without food, on a regular basis or in binges) or effects of different types of alcohol. They do not consider the complexity of factors related to obesity, and do not mention the effects of diet, exercise, smoking, or genetics on the risk of obesity. They misquoted the results of several previous studies to support their premise that lowering alcohol intake for everybody in the population would lead to less obesity, while a number of these studies actually showed the opposite.

Thus, the authors seem either oblivious to the data on alcohol calories and obesity or are deliberately ignoring it. Instead, their only concern appears to be to increase the incorrect perception that decreasing alcohol consumption among everybody, regardless of their intake, will lower the risk of obesity. Perhaps of even greater importance, they do not consider that a message to the entire population to decrease or stop alcohol consumption could result in increases in many diseases of ageing (e.g., coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, diabetes, premature mortality risk) that are reduced by regular, moderate intake of alcohol, especially when consumed with food.

The authors end with conclusions that relate obesity to the culture of shame: the pervasive misconception that obesity is primarily a lifestyle-related condition and the simplistic belief that weight reduction is just adopting permanent caloric restriction, and the failure of a person with obesity to achieve and maintain weight loss is caused by a lack of discipline.

Overall, the present paper appears to the Forum as potentially misleading in the sense that it diverts the attention of experts, and potentially the population at risk, from the far more important and above all actionable effort to recommend moderation in drinking associated with a healthy and active lifestyle that does not lead to weight gain.

Reference: Bowden J, Harrison NJ, Caruso J, Room R, Pettigrew S, Olver I, Miller CWhich drinkers have changed their alcohol consumption due to energy content concerns? An Australian survey. BMC Public Health 20222; 22:1775. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14159-9

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

======================================================

Critique 257: Does statin use modify potential beneficial effects of moderate alcohol consumption on cardiovascular risk? — 21 September 2022

The goal of this study was to determine if statin use (defined as the subject having been given a prescription for a statin, although actual consumption of statin was not ascertained) among a group of subjects who underwent cardiac catheterization modified the effects of alcohol consumption on subsequent cardiovascular events and total mortality. Their primary outcome was the occurrence during a follow-up period averaging 4.4 years of a Major Cardiac Adverse Event (MACE = documented myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, heart failure hospitalization, or all-cause mortality).

From their adjusted analyses for “primary prevention” subjects MACE outcomes were 6.5% for alcohol users versus 14.2% for alcohol non-users (HR 0.50, CI 0.33, 0.78) for those not on a statin. If the subjects were on a statin, the protection from alcohol was less (19.5% for alcohol users versus 22.7% for alcohol non-users), not statistically significant. For subjects classified as ‘secondary prevention,’ alcohol users had only slightly lower risk of a MACE outcome, 18.2% versus 19.9% for no statin users and 19.9% versus 22.7% for statin users, not statistically significant. (In the Authors’ abstract, the HRs reported as greater than 1.0 are apparently for non-users of alcohol versus users of alcohol, as the reported adjusted risk of MACE was lower for alcohol users in all categories.)

There were several problems identified in the Forum review regarding the study design, analysis, and conclusions of the authors. Subjects were from the Intermountain Medical Center with patients primarily from Utah and several surrounding states. The characteristics of the subjects are quite different from those in most other areas of the United States in that the large majority reported that they consumed zero alcohol (between 66% and 75% in the categories of subjects); this is probably related to most being of the Mormon faith where alcohol use is not acceptable. (Religious affiliation of subjects is not reported in the paper.) Further, it would be expected that many Mormons who may have had consumed some alcohol in the previous year would deny it on a form being collected by the Intermountain Center, where they are being treated; this would lead to under-reporting of the exposure being studied and misclassification.

Further, all subjects were placed into categories classifying them as at “primary cardiovascular risk” or “secondary cardiovascular risk”; also if they reported any alcohol use (regardless of the amount or the drinking pattern) they were classified as alcohol users; otherwise they were in the no alcohol category. Subjects with zero coronary obstruction on angiography were classified as being at “primary risk” if they had not previously reported a myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization procedure, or an obstruction of a coronary artery of ≥ 70% identified on a prior angiogram (n=477). Otherwise, regardless of current findings of coronary obstruction of zero or of any amount of obstruction greater than zero, subjects with a previous cardiovascular event (including ≥70% obstruction of a coronary artery on a previous catheterization) were classified as being at secondary risk (n=2,108). Such complex and unusual categorizations could lead to misclassification of exposure and various types of bias. No data that are based on all patients, regardless of classification into primary or secondary risk, are presented.

Unfortunately, in their main analyses there were no distinctions according to the reported amount of alcohol. They do report “exploratory analyses” of reported amount: those consuming < 2 drinks/day seemed to have the most protection from alcohol – however, the numbers of subjects in the groups were inadequate for definitive results. Further, there were no data on the “pattern of drinking” (regularly or sporadically, with or without food, etc.) for subjects reporting any alcohol use. Having all subjects evaluated only within categories could lead to bias and limits the usefulness of the results.

In their analyses, the authors adjusted the effects of alcohol use on MACE with an extremely long list of potential confounders. Unfortunately, among these was the presence of diabetes, for which alcohol consumption has clearly been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease; diabetes is considered to be an important intermediary mechanism of the effect of alcohol. Thus, it would not be appropriate as a confounder. Also, others of the factors included as potential confounders were those that would be expected to be affected (either adversely or beneficially) by alcohol consumption, thus should not be used as potential confounders if one is seeking to determine the total effect of alcohol on cardiovascular disease.

Overall, a number of factors weaken the implications cited by the authors. These include the database used for this study (a majority of subjects reporting zero alcohol at baseline, unusual for Western populations), problems in categorization of subjects into primary or secondary risk, inappropriate factors adjusted for as “confounders” (including some directly affected by alcohol use), failure to discuss the law of diminishing results, and suggesting “no effect” when results were not statistically significant. Such problems make it difficult to support the authors’ conclusion that the prescription of a statin negates any effect of alcohol consumption on cardiovascular risk.

Reference: Anderson JL, Le VT, Bair TL, Muhlestein JB, Knowlton KU, Horne BD. Is Alcohol Consumption Associated with a Lower Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Patients Treated with Statins? An Observational Real-World Experience. J Clin Med 2022;11:4797. doi.org/10.3390/jcm11164797

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

===========================================================

Critique 256: Alcohol consumption and health outcomes among 70 year olds in Sweden –22 August 2022

In a population-based cohort of 70-year-old men and women recruited in Gothenburg, Sweden, in 2014-2016, the authors of this paper have presented a detailed listing of many social, environmental, and biological factors that relate to non-drinking, former drinking, or current drinking of varying amounts of alcohol. Our Forum critique raises some questions about the traditional belief that the elderly should consume markedly less alcohol than younger subjects, and that the limitations placed on subjects related sorely to their age may often not be appropriate.

The paper emphasizes how a very large number of factors may modify the association between the amount of alcohol consumed and measures of health and disease. Many of these, such as indices of socio-economic state, are usually adjusted for in epidemiologic studies. Data on other factors that relate to alcohol consumption (such as self-related health, having a partner, grip strength, having others worried about their drinking, religiosity, gait speed, life satisfaction, etc.) represent data usually not collected in epidemiologic studies.

Forum members thought that these analyses show that subjects whose reported alcohol intake is only slightly above the recommended “safe” levels for subjects of this age should not be classified as “at-risk” drinkers. Most of their features match those of subjects reporting intake within current recommendations; certainly, they do not match the characteristics of heavier drinkers.

Forum members also pointed out that in addition to improved mortality associated with truly moderate drinking, as seen in essentially all epidemiologic studies, these analyses demonstrate that many other components of “successful ageing” are also associated with regular, moderate consumption of alcohol.

Reference: Ahlner F, Erhag HF, Johansson L, Fässberg MM, Sterner TR, Samuelsson J. Zettergren A, Waern M, Skoog I. Patterns of Alcohol Consumption and Associated Factors in a Population-Based Sample of 70-Year-Olds: Data from the Gothenburg H70 Birth Cohort Study 2014–16. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:8248; doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148248

For the detailed critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

=====================================================

Critique 255: Wine consumption and the risk of cognitive decline in the elderly – 29 June 2022

The results of this systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies showed that, in almost every study, both wine consumption within the usual guidelines (no more than 2 drinks/day for men or 1 drink/day for women), as well as consumption in excess of these limits, were similarly associated with a lower risk of cognitive decline. For studies providing data on the amount of alcohol consumed, the risk of cognitive decline was reduced by 41% for both wine consumers drinking within the recommended guidelines as well as those reporting wine consumption in excess of the guidelines, when compared with abstainers. In studies where the amount of wine consumption was not reported, the estimate was an 18% reduction in the risk of cognitive decline for wine consumers versus abstainers.

Forum members noted that many potential confounders of the relation of alcoholic beverage consumption and cognition may modify the effects of alcohol on cognition, and were not evaluated very well in this study. Especially important may be the pattern of drinking (regularly or irregularly, with or without food, with associated binge drinking, etc), Forum members agreed that the calculations of the authors support a protective effect of wine consumption against cognitive decline, but their conclusions may be limited because of residual confounding by the pattern of drinking and other key factors not included in their analyses.

Forum members also noted another recent paper relating brain MRI markers to alcohol intake. However, changes in cognitive function were not assessed in the latter paper, and a direct comparison between the two papers cannot be done. However, we conclude that there remain questions regarding the effects of wine and other beverages containing alcohol on cognition. Other studies have shown divergent effects on the risk of dementia associated with wine consumption and the intake of spirits, so there may indeed be different effects on cognition with wine intake, the factor studied in the present paper. And, when compared with non-drinking or drinking of other beverages, extensive research supports health and mortality advantages when wine is consumed moderately, and especially with meals.

Reference:Lucerón-Lucas-Torres M, Cavero-Redondo I, Martínez-Vizcaíno V, Saz-Lara A, Pascual-Morena C, Álvarez-Bueno C. Association Between Wine Consumption and Cognitive Decline in Older People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022;9:863059

For the full critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

=====================================================

Critique 254: Adjusting for underreporting of alcohol intake in epidemiologic studies – 13 April 2022

It has been demonstrated repeatedly that the total population alcohol consumption based on self-reports by subjects in surveys and epidemiologic studies is lower than the amount of alcohol sold or taxed (disappearance data) within the population. This is assumed to relate to marked underreporting of individuals of their consumption, sometimes by one half or more. A key problem in attempting to adjust the self-reported values to more closely match the total alcohol disappearance data is that everyone does not underreport their intake, or may do so by different degrees.

The present study was based on data from US adults who responded to the 2011-2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS; N = 2,198,089). The authors tested six methods for adjusting the self-reported data to provide what they hoped to be a more accurate value; some methods included adjustments based on differences in consumption by age and sex subgroups. From an unadjusted value of self-reported consumption of only 31.3% of that indicated by disappearance data, the various methods provided adjusted values ranging from 36.1% to 73%. The authors then used higher values to estimate the effect on alcohol-attributable deaths, using a population-attributable fraction approach.

While applauding the authors for attempting to obtain better estimates of alcohol consumption, Forum members were surprised that the authors did not even mention the method for identifying underreporting of individual subjects described by Klatsky and colleagues in the Kaiser Permanente Studies. The results of their method have been demonstrated to relate closely to alcohol’s effects on the risk of cancer, hypertension, and total mortality. Their method includes, in addition to self-reported data on alcohol consumption, adjustments for a variety of health conditions known to relate to excessive alcohol exposure, including alcoholic liver disease, hospitalizations for intoxication, mental problems associated with heavy drinking, etc. The presence of these conditions not only suggested that such subjects markedly underreported their intake (the exposure), but they also had much higher risk of adverse health effects (the outcome). When these conditions were not present at any of the study visits of subjects (allowing such subjects to be classified as being unlikely to be underreporting their alcohol consumption), adverse effects of low to moderate alcohol intake were generally not seen or their occurrences were markedly less frequent. This adjustment approach seems to be the only one previously described that gives reasonable results for individuals, and is clearly associated with the future health outcomes of subjects (and we realize that the occurrence of certain diseases or death happens for individual subjects, not for the population).

The Forum also raised questions about using “alcohol-attributable risk”. The authors base their calculations of population attributable risk on the hypothetic assumption of a rather low degree of underreporting in the population studies that are used as foundation of relative risk associations between alcohol intake and disease. Thus, risk is based mainly on self-reports of intake, even though their present paper indicates that adjustment for underreporting is so important. Further, throughout the paper, it appears that the authors tend to focus only on the adverse effects of alcohol without taking into regard the beneficial effects of light-to-moderate drinking, especially the regular consumption of wine with meals, which is found almost universally to be associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and total mortality.

While appropriate adjustment for underreporting could greatly improve the results of epidemiologic studies on alcohol and health, the goal would be to develop methods of determining the risk of individual subjects by including data on their own pattern of drinking and not assuming that the same adjustment formula applies to everyone in a population. By being able to identify subjects who underreport their intake, it would lead to some people changing categories of intake, and should result in estimates of either a lower risk, or greater risk, of adverse health effects of alcohol for that category of drinking. Further, more accurate and updated assessments of future health conditions that may be adversely (or beneficially) related to alcohol consumption should improve results and provide better data for setting drinking guidelines.

Reference: Esser MB, Sherk A, Subbaraman MS, Martinez P, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Sacks JJ, Naimi TS. Improving Estimates of Alcohol-Attributable Deaths in the United States: Impact of Adjusting for the Underreporting of Alcohol Consumption. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2022;83:134-144. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2022.83.134.

For the full critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

========================================================

Critique 253 – The relation of alcohol consumption to the risk of glioma tumors of the brain – 5 January 2022

There appears to be an increase in the risk of glioma tumors of the brain, yet very few lifestyle or genetic factors shown to be true “risk factors” for the disease have been identified. The authors of this paper present the association between reported alcohol consumption from multiple assessments over decades and the diagnosis of such tumors, combining data from subjects in large cohort studies of nurses and male health care providers. Among the important strengths of this paper is the fact that the data were collected as part of a prospective study, difficult to do in cancer epidemiology except with very large cohorts. A total of 554 cases of glioma tumors were identified in these cohorts from a total sample of more than 200,000 subjects.

Forum reviewers agree with the conclusions of the authors that light-to-moderate alcohol consumption does not increase the risk of glioma; in fact, total alcohol consumption over many decades was found to reduce the risk. For example, a cumulative average consumption of total alcohol of >8 to 15 g/d (approximately 0.5 to 1.0 drink/day) was associated with a 25% lower risk of glioma when compared with the lowest category of intake (0 to 0.5 g/day) for both men and women. For consumers of > 15 g/d (just over 1 typical drink/day) versus the referent group, the risk for women was further significantly reduced to HR = 0.61; for men, the HR estimate was 0.79, but not statistically significant. (Some previous cohort studies have suggested an increase in risk for heavy drinkers.) There were no differences according to type of alcoholic beverage. For the subgroup of subjects with glioblastomas, findings were similar but less precise, due to smaller case counts.

The Forum concludes that light-to-moderate alcohol consumption, versus no alcohol intake or very occasional drinking, does not increase the risk; in this very well-done study, such consumption showed a significant reduction in the risk of glioma tumors of the brain.

Reference: Cote DJ, Samanic CM, Smith TR, Wang M, Smith‑Warner SA, Stampfer MJ, Egan KM. Alcohol intake and risk of glioma: results from three prospective cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2021;36:965–974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-021-00800-1

For the full critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

========================================================

Critique 252: Dealing with previous alcohol exposure among “current non-drinkers” in epidemiologic studies testing the J-shaped curve – 3 December 2021

Most cohort studies have demonstrated a reduced risk of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and even dementia among light-to-moderate consumers of alcohol when compared with lifetime abstainers. This is often described as a “J-shaped curve,” a reduction in disease risk for light drinkers (compared with abstainers) but an increase in risk for heavy drinkers. Many criticisms of the J-shaped curve have been based on claims that many studies include “sick quitters” in their referent group. Such criticisms ignore most recent cohort studies in which only lifetime abstainers make up the referent group. Epidemiologists have known for decades that including ex-drinkers in the referent group for evaluating health effects of alcohol is an error; such a group cannot be used for comparisons with moderate drinkers.

While the present study from a large cohort in Germany clearly shows how previous alcohol excess and other unhealthy lifestyle factors and socio-economic factors influence the risk of many diseases, it creates a referent group made up of mixing lifetime abstainers and some ex-drinkers, and that their analyses show that this group does not have a higher risk of mortality than light drinkers (thus, the protection of light drinking leading to a decrease in risk of disease is erroneous). The authors of this paper apparently did this because they had such a small group of lifetime abstainers (only 42 subjects out of a cohort of 4,000!), a number grossly inadequate for comparisons with drinkers.

Forum members agreed that it was a serious error for the investigators; instead of admitting that their numbers were too low in this group for reliable comparisons, it appears that the authors augmented the comparison group with a group of ex-drinkers (that they considered to not be heavy drinkers) and reported that their analyses do not support a reduced risk among light drinkers. Thus, their claim that the lower risk of cardiovascular disease demonstrated in most studies among moderate drinkers is unrelated to alcohol consumption. However, this claim is based on an improper referent group used in their analyses. Forum members considered this to be a deeply flawed analysis, and of no merit for use in setting drinking guidelines.

Reference: John U, Rumpf H-J, Hanke M, Mayer C. Alcohol abstinence and mortality in a general population sample of adults in Germany: A cohort study. PLOS Med 2021;18:e1003819.

For the full critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

========================================================

Critique 251: Does moderate drinking increase, or decrease, the risk of falls in middle-age to elderly adults? 1 November 2021

To judge the relation of reported alcohol consumption to the risk of subsequent falls requiring hospitalization, the authors of this paper used data from the EPIC-Norfolk study, a prospective population-based cohort study in Norfolk, UK. In that study, there were a total of 25,637 community-dwelling adults, aged 40–79 years when recruited. The main outcome was the first hospital admission due to a fall over a follow-up period of about 11.5 years.

The key results of the study were that 19.2 % of non-drinkers were hospitalized for a fall during follow up, compared with 13.7% of low drinkers, 10.9 % of moderate drinkers, and 12.3% of heavy drinkers. In addition, the cumulative incident rates for falls at 121-180 months of follow up were 11.08% for teetotalers, 7.53% for low drinkers, 5.91% for moderate drinkers, and 8.20 % for heavy drinkers.

Forum members considered this to be a well-done study, with the analysis adjusting for a large number of factors that were potential confounders of the relation of alcohol intake to the risk of falls. We agree with the conclusions of the authors: “Moderate alcohol consumption appears to be associated with a reduced risk of falls hospitalization, and intake above the recommended limit is associated with an increased risk,” although we note that the increase in risk for heavier drinkers only appeared after essentially all covariates were added to the analysis. Obviously, residual confounding is always a possibility, but the present analyses indicating some protection against falls among light-to-moderate drinkers are supported by some well-done previous research.

The results of this study do not support the claim that any alcohol increases the risk of falls in older adults. It appears that this is not a concern for light-to-moderate drinkers who, in this study, had a lower risk of falls requiring hospitalization than did non-drinkers.

Reference: Tan GJ, Tan MP, Luben RN, Wareham NJ, Khaw K-T, Myint PK. The relationship between alcohol intake and falls hospitalization: Results from the EPIC-Norfolk. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2021;21:657-663.

For the full critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

========================================================

Critique 250: Importance of a favorable pattern of drinking (regularly, and with food) on risk of mortality – 28 July 2021

This is an analysis based on a very large data base of alcohol consumers (subjects reporting > 0 g of alcohol/week) from the UK Biobank (analyses based on 316,627 subjects with a median follow up of 8.9 years). The authors constructed categories of Drinking Habit Scores (DHS) for subjects; a “favorable” DHS was used for those subjects reporting a drinking frequency of 3 or more days/week and consuming alcohol with meals. The investigators then related the DHS categories to subsequent all-cause and cause-specific mortality, with adjustments for essentially all of the common known confounders/modifiers of alcohol effect.

Overall, Forum reviewers agreed with the main outcomes of the study, which indicate that subjects with a favorable DHS (in comparison with other drinkers) had significantly lower all-cause mortality (HR=0.82), CVD mortality (HR=0.84); cancer mortality (HR=0.82), and death from other causes (HR=0.77). In relation to the number of drinks consumed, the authors report that for all-cause, CVD, and other cause mortality, subjects with a favorable DHS showed a U-shaped or L-shaped curve (in that even for the heaviest drinkers, the mortality risk remained the same or lower than that of abstainers). Only for cancer mortality was there an increase in risk for subjects in the highest category of alcohol intake, leading to a J-shaped curve.

While the authors did not report specifically on the types of beverage being consumed in their favorable drinking pattern, it is the typical pattern generally found in southern Europe, and typically it is wine with meals. In these societies, wine is considered part of the meal, and is not consumed as “shots” that are usually being taken primarily as a way of getting drunk. As described in this paper, it is important to separate the health effects of these opposite approaches for consuming a beverage containing alcohol; putting all subjects into groups based only on the grams of alcohol consumed over a period, usually a week, does not take into account the important differences associated with the pattern of drinking.

We are finally appreciating that we are much further along in our research on alcohol and health than the innumerable studies that have focused just the amount of alcohol consumed, or on the J-shaped curve. We now realize the importance of the pattern of drinking. This constitutes not only the type of beverage and frequency of drinking, but also the consumption of alcohol with food and the absence of binge drinking. The pattern of drinking appears to be as important as, or even more important than, the quantity of alcohol consumed.

Reference: Ma H, Li X, Zhou T, Sun D, Shai I, Heianza Y, Rimm EB, Manson JE, Qi L. Alcohol Consumption Levels as Compared With Drinking Habits in Predicting All-Cause Mortality and Cause-Specific Mortality in Current Drinkers. Mayo Clin Proc 2021;96:1758-1769.

For the full critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

========================================================

Critique 249: Does light-to-moderate drinking increase the risk of atrial fibrillation? — 23 June 2021

While many epidemiologic studies have demonstrated an increase in the risk of AF for consumers of alcoholic beverages, there remains a question as to whether or not there is a threshold amount that would increase the risk. The present study concludes that “less than two alcohol units/day significantly increased the risk of incident AF, however, in men only. Reduction of even a moderate alcohol intake may thus reduce the risk of AF at the population level.”

While this may be the case, Forum members had a number of concerns about using the results of the present study to determine whether or not there is a threshold amount of alcohol necessary to increase the risk of AF. The methods used to judge alcohol consumption did not report the type of beverage or have a good estimate of the pattern of drinking, both of which factors are known to modify the health effects of alcohol. Further, the authors stated that there was evidence of considerable under-reporting of alcohol in their cohort, as the level of HDL noted in their “light” drinkers was above the level expected. This suggested to them that subjects in their lowest category of alcohol may actually have consumed more than they reported (probably about twice the reported amount of alcohol). This makes it difficult to determine if truly “light” drinking is associated with an increased risk of AF.

Overall, scientific data continue to show that light-to-moderate alcohol intake, especially when the pattern of drinking is found to be regular moderate consumption with food and without binge drinking, is associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke and death. For the effects of alcohol intake on the risk of AF, the situation remains unclear. Unfortunately, the present study cannot answer the question as to whether there is, or is not, a clear threshold effect of alcohol intake on the risk of developing AF.

Reference: Ariansen I, Degerud E, Gjesdal K, Tell GS, Næss O. Examining the lower range of the association between alcohol intake and risk of incident hospitalization with atrial fibrillation. IJC Heart & Vasculature 2020;31:100679.

For the full critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

================================================================

Critique 248: Association of Alcohol Consumption with Cataract Surgery — 19 April 2021

This was a well-done analysis of a very large number of cases of cataract surgery in the UK; there were reasonable measures of the exposure (alcohol consumption), including the amount and type of beverage consumed, and appropriate potentially confounding factors were taken into consideration. However, data on the consumption of alcohol with or without food were not available. The use of national registries of cataract surgery provide an appropriate approach for estimating the main outcome of the analyses, and the results probably reflect the incidence of clinically significant cataract occurrence in these populations.

The key results were that there was a small but highly significant lower risk of cataract surgery among moderate drinkers. Red and white wine consumers showed more consistent and significantly lower risks of cataract surgery than consumers of other beverages. (In one of the two studies included in the analysis, small amounts of beer and spirits also showed a lower risk than that of non-drinkers.) There were too few heavy drinkers in these studies to determine the extent to which such drinking might affect risk. We appreciate that residual confounding, especially by factors that relate to subjects choosing to have surgical treatment of their cataracts, could still be present in these results.

Forum reviewers conclude that, in agreement with the investigators of this study, the data indicate a small but statistically and clinically significant decrease in the risk of cataract surgery for low-to-moderate drinkers, versus non-drinkers. A lowering of risk was especially clear for wine drinkers, in comparison with consumers of beer and spirits. There is an extensive literature regarding potential mechanisms by which constituents of the diet, especially those present in wine, may influence the development of cataracts. Among these are antioxidants or ROS scavengers, aldose reductase inhibitors, antiglycating agents, and inhibitors of lens epithelial cell apoptosis. However, the ultimate reason for the lower risk of cataract surgery associated with wine consumption found in this study has not been clearly delineated.

Reference: Chua SYL, Luben RN, Hayat S, Broadway DC, Khaw K-T, Warwick A, et al, on behalf of The UK Biobank Eye and Vision Consortium. Alcohol Consumption and Incident Cataract Surgery in Two Large UK Cohorts. Ophthalmology 2021, pre-publication.

For the full critique of this paper by the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research, please click here.

================================================================

Critique 247: Effects of alcohol consumption on risk of stroke and systemic embolism among subjects with atrial fibrillation – 15 March 2021

The main aim of the current study was to investigate the associations of regular alcohol intake with incident stroke or systemic embolism in patients with established atrial fibrillation (AF), most of whom (84%) were on anti-coagulant therapy. The authors used combined data from two prospective studies of subjects with AF, followed for an average of 3 years. While they excluded subjects with “only short, potentially reversible AF episodes (e.g., as after cardiac surgery or sepsis)” about one half of subjects in the study were diagnosed as having paroxysmal AF. Reported alcohol at baseline and at subsequent examinations was classified as none, > 0 to < 1 drink/day, 1 to < 2 drinks/day, and ≥ 2 drinks/day.

The primary outcome was a composite of stroke and systemic embolism. Secondary outcomes were all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, hospital admission for acute heart failure, and a composite of major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding. In their analyses, they adjusted for age, sex, education, hypertension, history of heart failure, history of diabetes, BMI, smoking status, physical activity, history of stroke, history of coronary heart disease, oral anticoagulation, history of renal failure, AF type, and health perception. With annual assessments, the investigators updated all covariates over time, if appropriate.

The main results indicated no significant effect of alcohol consumption on the risk of the major outcomes (stroke or systemic embolism). However, there were significant decreases in risk for several secondary outcomes. For hospital admissions for heart failure, in comparison with non-drinkers the HR for moderate drinkers was 0.60 (CI 0.41-0.87); further, among moderate drinkers the HR for myocardial infarction was 0.39 (CI 0.20 – 0.78), and for all-cause mortality the HR was 0.49 (CI 0.35-0.69).

Forum members had two major concerns with the paper. First, the authors failed to report specifically how alcohol consumption was associated with increased or decreased presence of AF during follow up, even though approximately one-half of subjects had only paroxysmal AF at baseline. Determining if alcohol consumption affected subsequent AF would be information of importance to practitioners who are advising their patients with AF regarding alcohol consumption.

Secondly, it was pointed out by Forum members that the results may have been affected by what is known as collider bias: as moderate drinking shows an inverse association with coronary heart disease (which is strongly related to the presence of AF), subjects who consumed alcohol prior to the baseline diagnosis of AF were probably different from those who had no prior alcohol exposure, and the results of combining these two groups (as was done in these analyses) may have been biased. Such bias usually tends to result in estimates of effect going toward the null.